Long-Term Exposure to PM2.5 Pollution Raises Diabetes Risk in Middle-Aged People

Dr JK Avhad MBBS MD [Last updated 15.12.2025]

Type 2 diabetes has traditionally been linked to diet, physical inactivity, obesity, and genetics. However, a growing body of U.S. and global research suggests that environmental exposure—especially long-term exposure to PM2.5 air pollution—plays a significant role in diabetes risk, particularly among middle-aged Americans.

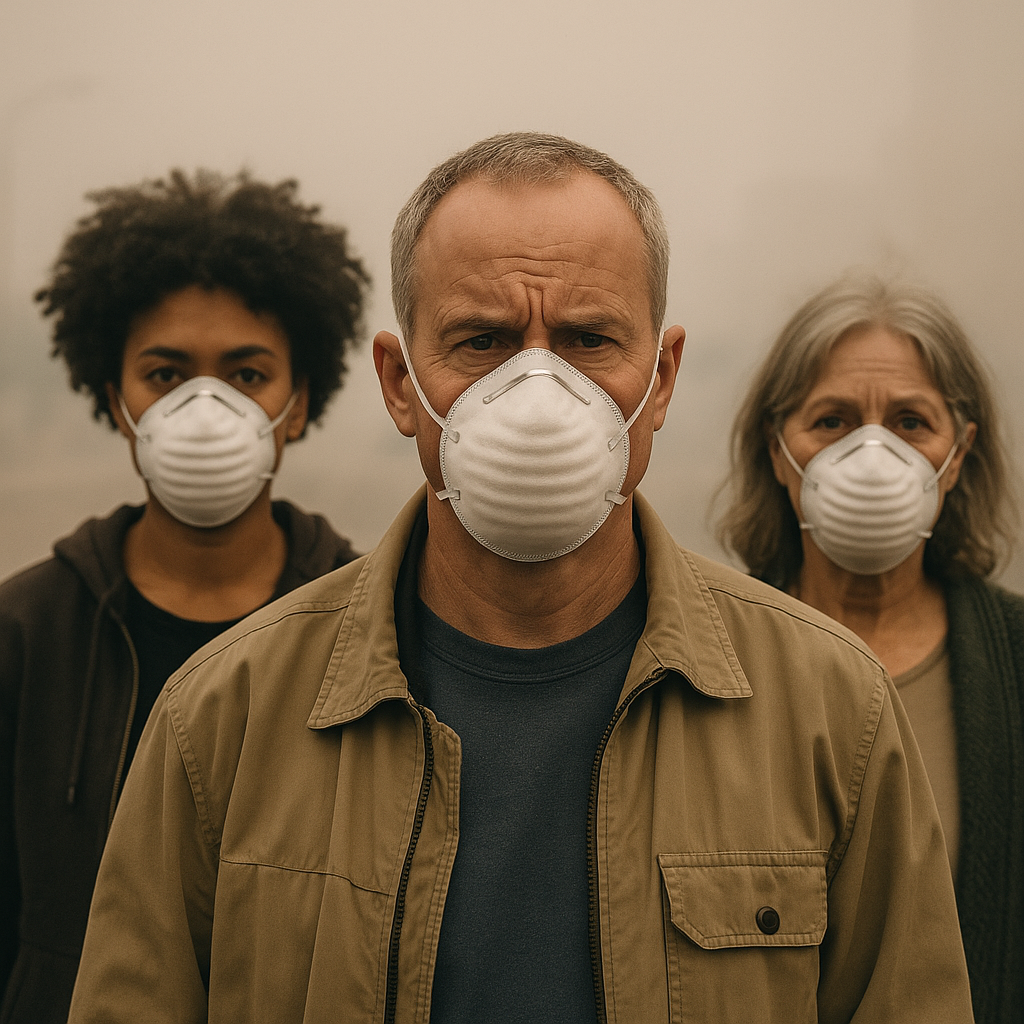

PM2.5 refers to particulate matter smaller than 2.5 micrometers—about 30 times thinner than a human hair. These particles come from vehicle exhaust, coal and gas power plants, industrial emissions, construction dust, and wildfire smoke. Because of their tiny size, PM2.5 particles bypass the body’s natural defenses and enter the bloodstream, affecting organs far beyond the lungs.

Long-term exposure to PM2.5 air pollution is emerging as a silent but powerful risk factor for type 2 diabetes among middle-aged Americans.

Fine particulate matter, produced by traffic, industrial emissions, wildfire smoke, and fossil fuel combustion, penetrates deep into the lungs and bloodstream, triggering chronic inflammation, insulin resistance, and metabolic dysfunction.

Growing evidence from U.S. cohort studies, CDC-linked data, and NIH-funded research shows that adults aged 40–65 living in polluted regions face significantly higher diabetes risk—even without obesity or family history.

In the U.S., millions of adults aged 40–65 live in areas where PM2.5 levels regularly exceed recommended limits. Many of them have no idea that the air they breathe daily may be quietly increasing their risk of diabetes.

Also read: How Does Climate Change–Driven Heat Increase the Risk of Kidney Stress and Dehydration Among Working-Class Americans?

[ Click here: https://healthconcise.com/elementor-2488/ ]

PM2.5 (fine particulate matter) is considered one of the most harmful air pollutants due to its ability to penetrate deep into lung tissue and circulate systemically.

Common Sources of PM2.5

· Highway and urban traffic emissions

· Diesel trucks and freight corridors

· Coal, oil, and natural gas power plants

· Wildfire smoke (increasing with climate change)

· Industrial manufacturing zones

· Residential wood burning and gas stoves

According to the World Health Organization, there is no safe level of long-term PM2.5 exposure (WHO, 2021).

Middle age (roughly 40–65 years) represents a metabolic tipping point. During this period:

· Insulin sensitivity naturally declines

· Visceral fat increases even without weight gain

· Blood pressure and cholesterol begin to rise

· Physical activity often decreases due to work demands

When chronic PM2.5 exposure is added to these age-related changes, the risk of developing type 2 diabetes increases significantly—even in non-obese individuals.

Large U.S. cohort studies have shown that middle-aged adults living in high-PM2.5 regions develop diabetes earlier and more frequently than those in cleaner environments.

PM2.5 and Insulin Resistance

Chronic Systemic Inflammation

Once inhaled, PM2.5 particles:

- Enter alveoli in the lungs

- Pass into the bloodstream

- Activate inflammatory immune pathways

This leads to persistent low-grade inflammation, a key driver of insulin resistance.

Inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein (CRP), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and TNF-α interfere with insulin signaling at the cellular level, making it harder for glucose to enter muscle and liver cells.

NIH-funded studies have repeatedly shown that chronic inflammation is a central mechanism linking air pollution to metabolic disease (NIH, 2022).

Oxidative Stress and Cellular Damage

PM2.5 particles generate reactive oxygen species (ROS), which damage:

- Pancreatic beta cells (responsible for insulin production)

- Mitochondria (energy regulation)

- Vascular endothelium

Over time, this oxidative stress reduces insulin secretion and worsens glucose regulation.

Disruption of Adipose (Fat) Tissue Function

Air pollution alters how fat tissue behaves. Studies in U.S. adults show that PM2.5 exposure:

- Increases visceral fat inflammation

- Changes adipokine release (leptin, adiponectin)

- Promotes insulin resistance even without obesity

Also read: How to Boost Immunity Naturally at Home

[ Click here: https://healthconcise.com/elementor-2353/ ]

PM2.5 and Diabetes Risk

- A large U.S. study of over 1.7 million adults found that every 10 µg/m³ increase in PM2.5 was associated with an 8–15% increase in diabetes incidence (CDC).

- Even PM2.5 levels below current EPA standards were associated with higher diabetes risk.

- NIH-supported research showed higher diabetes prevalence in communities near highways, industrial zones, and freight corridors.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, more than 37 million Americans have diabetes, and environmental factors are increasingly recognized as contributors (CDC, 2023).

Traffic Pollution Is a Major Contributor

Traffic-related air pollution deserves special attention because:

- It is continuous and unavoidable

- It disproportionately affects urban and lower-income communities

- It contains ultrafine particles with high inflammatory potential

Middle-aged Americans living within 300–500 meters of major roadways show higher rates of insulin resistance and prediabetes compared to those farther away.

Climate Change Is Worsening PM2.5 Exposure

Climate change intensifies PM2.5 exposure through:

- More frequent and severe wildfires

- Longer ozone and pollution seasons

- Increased heat that enhances pollutant toxicity

Wildfire smoke, in particular, contains highly inflammatory PM2.5, and repeated exposure has been linked to short-term spikes in blood glucose levels in adults with and without diabetes.

Higher Risk Groups

- Adults aged 40–65

- People with prediabetes or metabolic syndrome

- Residents of urban or industrial regions

- Outdoor workers (construction, delivery, utilities)

- Individuals with low access to green spaces

Genetics still matter, but environmental exposure can amplify genetic risk.

One of the most important findings in recent research is that PM2.5:

- Raises fasting glucose levels

- Increases HbA1c over time

- Worsens insulin sensitivity

This occurs independently of BMI, challenging the traditional belief that weight alone explains diabetes risk.

Also read: What Is Causing Your Bloating? Reasons for a Distended Abdomen.

[ Click here: https://healthconcise.com/elementor-2325/ ]

How to reduce the Risk

Personal-Level Strategies

- Use indoor air purifiers with HEPA filters

- Avoid outdoor exercise during high AQI days

- Improve indoor ventilation while reducing outdoor pollutant entry

- Monitor blood glucose if living in high-pollution areas

Community & Policy Awareness

- Support clean air initiatives

- Advocate for reduced traffic congestion near residential zones

- Promote urban green spaces

While individual actions help, population-level air quality improvements have the greatest impact.

FAQ’s:

Q. Does air pollution really cause diabetes or just worsen it?

· Evidence suggests PM2.5 can contribute to the development of diabetes, not just worsen existing disease, by triggering inflammation and insulin resistance.

Q. Can living in a polluted area increase diabetes risk even if I eat healthy?

· Yes. Studies show increased diabetes risk even among physically active, normal-weight individuals exposed to long-term PM2.5 pollution.

Q. Are rural Americans protected?

· Not always. Wildfire smoke, agricultural burning, and power plants can expose rural populations to high PM2.5 levels.

Q. Is PM2.5 exposure reversible?

· Reducing exposure can improve insulin sensitivity over time, but prolonged exposure may cause lasting metabolic changes.

Conclusion:

For middle-aged Americans, diabetes risk is no longer explained by lifestyle and genetics alone. Long-term exposure to PM2.5 air pollution is a scientifically supported, biologically plausible, and increasingly urgent contributor to metabolic disease.

As climate change, urbanization, and traffic pollution intensify, recognizing air quality as a diabetes risk factor is essential for prevention, early screening, and public health planning. Cleaner air is not just a respiratory issue—it is a metabolic necessity. Air pollution is a metabolic risk factor, we can no longer ignore.

This article is for informational purpose only and does not substitute for professional medical advise. For proper diagnosis and treatment seek the help of your healthcare provider.

References:

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023). National diabetes statistics report.

- World Health Organization. (2021). WHO global air quality guidelines.

- National Institutes of Health. (2022). Air pollution and metabolic disease research summary.

- Brook, R. D., et al. (2017). Air pollution and cardiometabolic disease. Circulation, 136(5), 416–431.

- Rajagopalan, S., et al. (2018). Ambient particulate matter and insulin resistance. Diabetes, 67(6), 1190–1201.

- Bowe, B., et al. (2018). The 2016 global burden of diabetes attributable to PM2.5. The Lancet Planetary Health, 2(7), e301–e312.

- Pope, C. A., et al. (2015). Fine particulate air pollution and mortality. New England Journal of Medicine, 373, 157–168.

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (2022). Integrated science assessment for particulate matter.

- Eze, I. C., et al. (2015). Association between air pollution and diabetes. Environmental Health Perspectives, 123(7), 674–681.

- Liu, C., et al. (2019). Air pollution and glucose metabolism. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 104(10), 4530–4540.